As a general rule, I don’t think that the world is comprised of good and evil.

Just as the great twentieth-century theologian, Martin Buber, divided the world into the “holy and not-yet holy,” I think that the majority of people fall into the “good and not-yet good” categories. Or, at the very least, that is how we can understand their actions.

Evil does, and always has, existed in our world.

I’m talking about true evil.

Not just the swindlers, scoundrels, and cheats.

But those who do the unmentionable. The inconceivable. The heinous.

A cursory glance at our history proves this to be true.

Roman persecution.

The Crusades.

The Inquisition.

Khmelnytsky Uprising.

Pogroms.

The Shoah.

We could choose to “put the past behind us.” To “forgive and forget.” To “get over it.”

We could choose to “dwell on the past.” To take on a “victim mentality.”

But there is another alternative.

To recall those catastrophic experiences and find the good.

Not find meaning in them.

But seek the goodness.

Those individuals, named and unnamed, who risked their own lives to help us.

Those individuals, named and unnamed, who managed to maintain their dignity and faith in the midst of the horror.

The Yom Kippur liturgy, for those of Ashkenazic descent, includes a section known as Eleh Ezkerah. Named for the opening words, the Midrashic-based poem details the martyrology of ten rabbis during the period of Roman persecution under the rule of Hadrian. In Gates of Repentance, the High Holy Day prayerbook of the Reform movement, this section is read during Yom Kippur afternoon. When we are weary, physically and emotionally. We are hungry and thirsty. This section, rather than dragging me down, always lifts me. It is a reminder that others have suffered so that I may live. Freely as a Jew. It is a reminder to preserve that which was denied so many who came before me. It is reminder that there is good in the midst of evil.

**********************

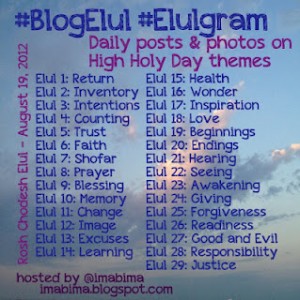

This post is part of #BlogElul — a project, created and oordinated by The Ima, in preparation for the start of the New Year, Rosh Hashanah. Feel free to head over to her place and thank her for dreaming up such a creative way for us to consider the different themes associated with the Jewish High Holy Days.

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning is my favorite example and explanation of this idea. Thanks for the reminder.